This story is the first part of the Martimoaapa history series. The series recounts the history of Martimoaapa and its surrounding area from ancient times to the present day, highlighting signs and memories that are still visible to travelers in the terrain, serving as reminders of times past.

The highest points of the Penikkavaara hills emerged from the sea during the early Stone Age, and ancient settlements, stone structures, and quartz quarries have been discovered in the Martimoaapa area. Large boulders several meters high in the middle of the forest. Extensive cairn fields on the slopes of Keski-Penikka. Peculiar stacked stone circles in the middle of the wilderness. Did the ancient giants hurl those stones into the forest? Or is it the devil himself who, to torment poor humans, has scattered stones on the slopes of Kivalo?

In the footsteps of the Jatuls

According to the tale recounted in Simo, the giant folk were said to have originated at a time when the shores of the sea were still nearly deserted, and people lived inland. Giants, or Jatuls as they are known here in the Sea Lapland, initially drove the inhabitants of the shores into the forests and settled the coastline of the Far North, but over the years people moved back closer to the sea and eventually cursed the Jatuls to the Kivalo hills. The Jatuls roamed and dwelled around the Penikkavaara and Martimoaapa areas. Thus began the Kivalo giants, who are perhaps the most famous giants in the Far North region.

It is said of the Jatuls that they were a giant folk. They had supernatural abilities and dwelled in caves and hollows. The Jatuls cared little for unnecessary noise; the sounds of human life annoyed them, cowbells enraged them, and the churn’s splash disgusted them. People could entice the strong and simple giants to even build churches, but when the church bells rang, the giants fled in anger.

The last giants of Keminmaa were Kilka, Kalli, and Jatuli. Even after they had fled to the shores of the Arctic Ocean, people still spoke of giants haunting the regions of the Sea Lapland. According to the tale, the giants were said to have left their treasure of gold in Kivalo, but they cursed it as they departed. If a traveler took that gold into their pocket, they would no longer find their way home. Therefore, the treasure must be returned and left in its place where it was found, if one wished to find their way home.

Vocabulary:

- Ancient monument: a structure or deposit preserved in the landscape, soil, or underwater, resulting from the activities of people who lived in the past.

- Archaeological survey: a systematic field investigation involving the examination of previously known ancient monuments and the search for new sites.

- Prehistoric period: the time before the 14th century and before written sources.

- Historic period: the time after the 14th century when written sources are available.

- Stone Age settlement: a site with signs of Stone Age habitation, which may consist of both permanent and non-permanent ancient monuments.

- Stone pit (rakkakuoppa): a pit dug into rocky ground, surrounded by a circular embankment. Cairns have been used, among other things, for storing meat. A fixed ancient monument.

- Quartz quarry: a quarry from which quartz was mined during the Stone Age. Quartz was used as a tool material. A fixed ancient monument.

- Quartz flake: a piece or fragment of quartz resulting from the manufacture of Stone Age quartz objects. A non-fixed ancient monument.

- Jatuli: According to legend, a race of giants that lived in the Sea Lapland.

- Jätinkirkko: Jatuli’s Church, a large, circular or rectangular stone enclosure. A fixed ancient monument.

Seal hunting on the Penikka Islands

In the Martimoaapa area and the surrounding Penikkavaara region, there are many places whose names refer to giants, and stone structures and pits have been found in the area that are believed to be the work of giants. Some of the place names include Kilkanjänkä, Jatulin lammet (currently Myllylän lammet), Jatulinoja, Jatulinlehto, and many others. Whether one believes in giants or not, these ancient stone structures and rocky fields appear strange to modern-day people.

Let’s take a moment to travel back to ancient Finland. What kind of the area of Peräpohjola and Martimoaapa be like thousands of years ago? Well, of course, we can only speculate, but some things are known.

The highest points of Penikkavaara emerged from the sea in the early Stone Age, forming islands. The shores of these islands were vulnerable to the powerful waves of the sea, and as a result of both land uplift and the onslaught of poisonous waves, coastal ridges formed on the slopes of Penikkavaara. On the upper slopes of Penikkavaara, these coastal deposits consist of large rocks and boulders.

These islands formed as a result of land uplift attracted fishermen and seal hunters to the area. Ancient human life was very seasonal and focused heavily on obtaining food. Summers were spent moving around, while winters were more stationary. In summers, people fished, hunted birds, and pursued game. In winters and autumns, seal hunting was practiced at sea. Low stone walls were erected on the shores as shooting shelters for seal hunting and bird hunting, remnants of which are still visible in the terrain throughout the Peräpohjola region.

Over time, land uplift has shifted the seafront to its current location, more than 20 kilometers away from Penikkavaara. Consequently, settlement gradually declined on the Penikkavaara and its surrounding areas as the land became more swampy due to uplift. Settlements moved closer to water bodies: the Perämeri sea, Kemijoki River, and Simojoki River.

Traces from the past

In the Martimoaapa area, there are abundant traces likely dating back to prehistoric times, i.e., before the 14th century, as a testament to the activities of ancient people. From these times, there are no written sources, so we cannot read about life in ancient times from books or newspapers; we can only infer the course of life based on ancient monuments. Ancient monuments are indeed the only evidence of life and people from that time.

Several archaeological surveys have been conducted in Martimoaapa at various times. Archaeological surveys aim to assess the condition of ancient monuments and may also search for new archaeological sites. The oldest surveys encountered in the Penikkavaara area date back to 1877 (Appelgren) and 1894 (Castrén). It was not until 100 years later that surveys continued when basic surveys of municipalities began in Finland. The latest research can be found in the National Board of Antiquities’ Kyppi (Cultural environment service window in Finnish) service. The most recent survey was conducted in 2007, with inspections conducted thereafter as well.

Shingle beaches

It should be mentioned here between the devil’s fields or shingle fields. They are familiar sights to travelers in Martimoaapa, especially those who have visited the Kivalo wilderness hut. Devil’s fields got their name from the belief that the devil himself would have thrown the stones into place or that the devil wanted to defy God’s will and chose a rocky area as his farmland. However, according to natural science, devil’s fields are formed from moraine released by continental glaciation. These ancient shoreline stone fields were formed approximately 2,000 to 12,000 years ago and are usually located on the tops of hills or gentle slopes.

So, devil’s fields are natural formations of ancient shoreline stone fields, not ancient monuments, but rocky fields were important places for ancient humans. Therefore, most of the ancient monuments found in the area are located in the cairn fields of Penikkavaara. Small stone stacks may have been made in rocky areas as boundary markers or sacred sites, or pits may have been dug for various purposes. Raw materials for making tools have also been taken from rocky fields. There are magnificent devil’s fields on the slopes of Penikkavaara and Koivuselkä, which can be admired along hiking trails.

In the southern part of Penikkavaara, west of Kaltiolampi, and on the western side of Pookijänkä, quartz quarries have been found in the cairn fields. The quartz boulders show signs of processing, and quartz has been extracted from them. There are naturally many quartz boulders in the cairn fields of Penikkavaara, which ancient travelers have already utilized for making various tools.

Pits have also been found in the Penikkavaara area. These pits were used for storing meat, and some of them were built over hidden streams. The cold water from the streams kept the pits cool even in the summer, thus serving as ancient refrigerators. These pits are also known as “jätin jääkaappi” (giant’s refrigerator) or “purnu.” Pits built over hidden streams have been found, for example, on the western side of Pookijänkä and on the southern slope of Ala-Penikkavaara.

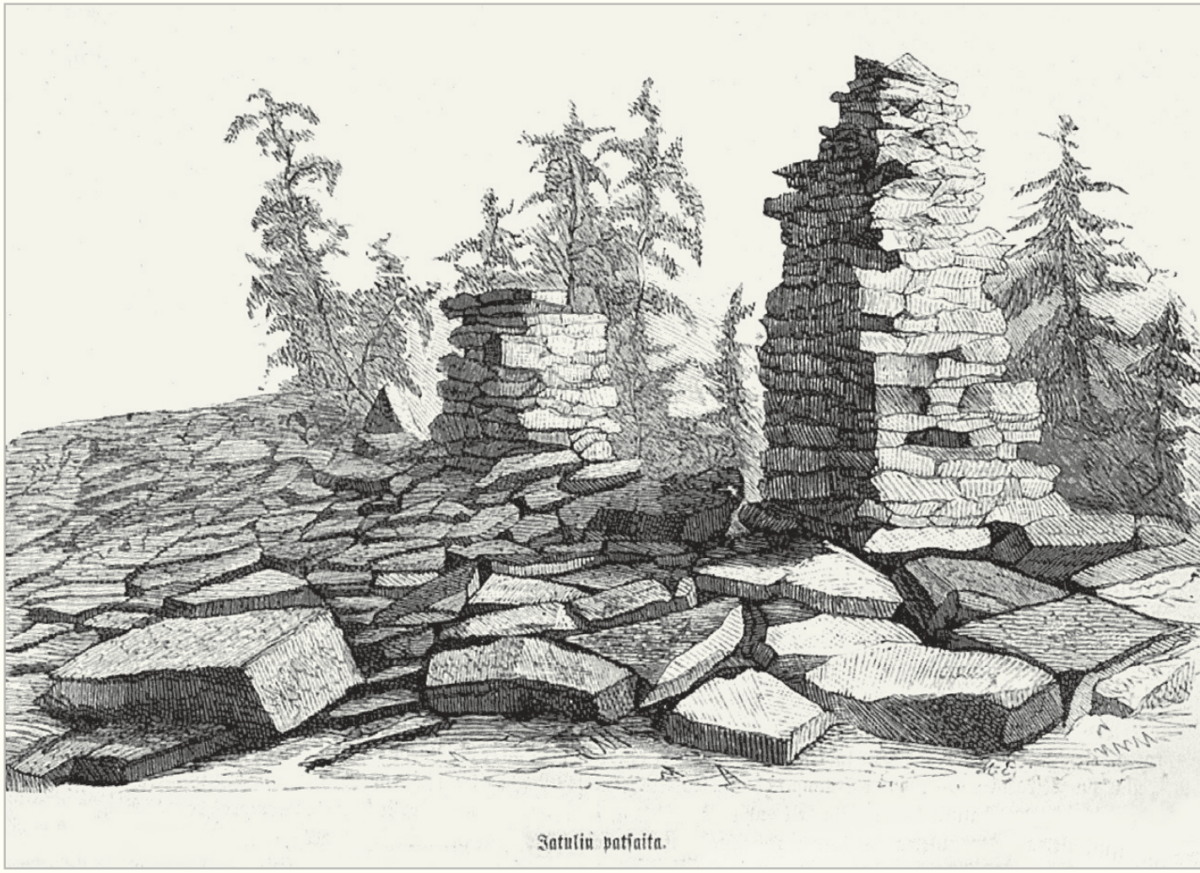

Between Ala-Penikka and Keski-Penikka, north of Helkkusen vaara, on the rocky Tornivaara, the remnants of two giant pillars have been preserved. The giant pillars are stacked stone columns. Originally, there were three giant pillars; the middle one was taller, and the other two were smaller. The largest pillar was about two meters high, and the smaller ones were about one and a half meters high. Unfortunately, over time, the pillars have been destroyed, and only the bases remain. Legend has it that some kind of worship was held at the site in ancient times.

As one walks along the rocky slopes of Penikkavaara, it’s not the first thing that comes to mind that someone might have once moved or even lived there thousands of years ago. As mentioned earlier, archaeological studies and surveys in the Martimoaapa area have revealed ancient settlement sites, stone structures, and quartz quarries. Nearly thirty pit ovens have also been discovered in the area, along with the stone circle of Jatulilehto on the eastern side of Yli-Penikka.

Ancient settlement sites

The Sámi people were indigenous peoples who roamed and lived in the Northern Fennoscandian region already in the early Stone Age. Evidence of their lifestyle, hunting methods, and culture has been found across Lapland, spanning over current state borders. The term “Sámi” thus referred to all inhabitants of remote areas who earned their livelihood through hunting and fishing. The term “Sámi” encompasses more than just the Sami people.

People in ancient times were skilled hunters. Harpoons, spears, and clubs were used as weapons for hunting. Birds, on the other hand, were also caught with bows and slingshots. Stone, including quartz, as well as wood and various bones, were commonly used in the production of hunting tools.

Food was prepared by roasting on hot stones, in wooden bowls, and later in clay bowls. Food items were also dried and preserved for difficult times and for traveling provisions. The diet consisted mainly of vegetables, fish, and game. Sometimes, small-scale cultivation was practiced near settlements. Seeds were grown among other vegetation or small fields were cleared for cultivation.

Settlements were usually located near water bodies, river estuaries, and hunting grounds. Although people moved around a lot at that time, they often wanted to return to the same settlement if food was available there. Ancient humans were entirely dependent on fishing, hunting, and gathering. Dwellings were constructed from wood, moss, and other natural materials, and as a result, the structures themselves have been poorly preserved. However, remnants of food preparation, stone processing, and changes in the soil remain at the settlement sites.

Archaeological excavations have uncovered residential sites, evidenced by fragments resulting from stone processing, burnt fish bones, and pieces of clay pots. Remnants of stone-built dwellings have been preserved. Discoveries have been made in at least three ancient residential sites in the Martimoaapa area.

A Stone Age residential site has been found in Myllyaho. Myllylänaho is located between Myllylänaava and Simoskanaava, north of Hangassalmenaho, and rises to a height of approximately 97 meters above sea level. Unfortunately, most of the remnants of the residential site have been destroyed due to gravel extraction.

Another Stone Age residential site has been discovered on the northern slope of Yli-Penikka. Signs of a Stone Age residential site were found at the southern edge of a sand pit; slate flakes, burnt bones, and stones were discovered. Based on the location and elevation of the site, it may have been in use as early as 8700–5100 BCE. Unfortunately, the remnants of this site have likely been destroyed, possibly due to sand extraction.

Remnants of two residential sites have also been found in Ala-Penikka. Near the summit of Ala-Penikkavaara, there is a stacked circular wall suggestive of a dwelling. The wall is located on the western edge of a rockslide and is oval-shaped. There are openings at both ends of the wall as if for passage. The stones of the wall have a diameter of approximately 20-40 cm, and there are small fist-sized stones on the floor. In the center of the circle, there is a large fireplace. Remnants of another possible residential site have been found on the southeast slope of Ala-Penikka. Three pit ovens have been discovered on the slope, one of which is surrounded by low walls ranging from 20 to 59 cm in height.

Jatulinlehto: Ancient stone ring wall

In the 1800s, a large approximately 4 x 2 meter ring wall was excavated and stacked in Jatulinlehto, east of Yli-Penikka. The ring wall is currently located near the boundary of the conservation area. Similar ring walls have been found in Tornio.

The corners of the ring wall are rounded. The walls are almost one and a half meters wide and about 70 cm high. The ring is surrounded by a wide spread of boulders. In the 1877 survey, according to archaeologist Appelgren, the walls of the ring would have been higher at that time, “so that an average man could reach the top,” and there would have been an altar inside the ring, a kind of tabletop, which “reached above a man’s knee.” Appelgren speculated that there may have been a wooden roof over the ring, which has since fallen down.

Next to the large stone circle is also a smaller ring wall, about two meters in diameter, with only a few layers of stones on the sides. Many burnt stones have been found in the vicinity of the stone circles, which are likely related to food preparation, as well as about ten pit ovens.

The walls of the Jatulinlehto stone circle are constructed using dry stone walling technique, where larger stones are arranged tightly with the help of smaller wedge stones. The stone circle is marked in the ancient monument register as a giant’s church, but compared to other known giant’s churches, here the stones are laid more precisely rather than stacked, as is typical for giant’s churches.

Around 6500 BCE, the location was a small island. If this stone wall were from that time, the structure would be over 8500 years old. The exact purpose of this stone circle is not entirely certain. It is believed to have been either a dwelling place for seal hunters or a base for seal hunting. According to another theory, the ring wall could have been a wolf trap; a bait would have been placed on the altar in the center of the circle to lure a wolf inside, where it could then be easily captured.

Jatulinlehto is also known as the Island of Jatulis, where the last giants of Peräpohjola are said to have resided. We visited Jatulinlehto in the summer of 2023 while mountain biking on a hiking trail (story in Finnish). The place was truly impressive. I have never seen a similar structure anywhere else.

The Ancient Monuments Act (295/1963) protects immovable ancient monuments. Without permission granted under the law, no one is allowed to, for example, excavate, cover, dismantle, damage, or alter in any way an ancient monument area. This ensures that ancient monuments and their associated history are preserved as well as possible.

Encountering an ancient monument

Ancient monuments can be encountered by hikers, especially in the Penikka Hills area and at Jatulinlehto, which contains several pit caves and quartz quarries within its rocky outcrops. Under the Everyman’s Right, visitors can access ancient monuments, but they must ensure not to cause any harm or damage to the site.

A responsible hiker walks and acts in a way that does not damage the ancient monument or its surroundings. They do not stack or move rocks, take souvenirs, or pick plants from the vicinity of the ancient monument. This helps keep the area clean, prevents damage to vegetation and structures, and ensures the preservation of ancient monuments for the future.

As the shoreline gradually moved 20 kilometers away from the Penikka Hills over the years, turning the surrounding areas into marshlands, did the area become completely deserted? Was the bear the only traveler in the Middle Ages in these marshes? You might find answers to these questions in the next part of the “Martimoaapa History” blog post.

Read next: Martimoaapa history part 2

Sources and more info:

- Paahde-LIFE –alueiden kulttuuriperintöinventointi Sota-aavan ja Martimoaavan-Lumiaavan-Penikoiden soidensuojelualueilla 2014 ja Joutensuon Natura 2000 -alueella 2015, Metsähallitus

- Martimoaapa history, Nationalparks.fi, Metsähallitus

- The National Library of Finland

- Kultuuriympäristön palveluikkuna, The Finnish Heritage Agency

- Arkeologisen kulttuuriperinnön opas, Museovirasto

- Torniolaakson argeologiaa, Kalmistopiiri, Arkeologinen verkkojulkaisu

- Jättiläisten valtakunta. Jättiläistarinat osana Suomen kiinteitä muinaisjäännöksiä, Anna Hyppönen, 2016 Oulun yliopisto

- Muinaismuistolaki, Finlex.fi

- Circling Concepts – A Critical Archaeological Analysis of the Notion of Stone Circles as Sami Offering Sites, Marte Spangen, 2016 Stockholm University

- Zach Castrén: Vanhan ajan muistoja Kemin, Tervolan ja Simon seurakunnista, 1894 Helsinki

- Muinais-tiedustuksia Pohjanperiltä, J. W. Calamnius, 1868

Translated with ChatGTP

Write a comment