This story is the second part of the Martimoaapa history series. The series recounts the history of Martimoaapa and its surrounding area from ancient times to the present day, highlighting signs and memories that are still visible to travelers in the terrain, serving as reminders of times past.

After the Ice Age, land uplift moved the sea shore kilometers away from Penikkavaara, but at the same time, it transformed the surroundings of the hills into a paradise of marshes. Ancient people moved along with the shore further away, and so the area was taken over by boglands, marshes, bears, martens, and other creatures of the wilderness. However, there were still plenty of other wanderers in these rugged backwoods.

Wanderers of the wilderness

The Lapland people wandered and lived in the Peräpohjola region as early as the Stone Age. The term “Lapland people” thus referred to all inhabitants of remote areas who earned their livelihood through hunting and fishing. The Lappi people designation therefore includes more than just the Sami people, but in the Martimoaapa area, there are many place names derived from the Sami language, such as Maaninkajärvi and Martimojärvi. “Martimo” means “sable” in Lapland, referring to the marten.

Settlement initially concentrated around the mouths and banks of the Kemijoki and Simojoki rivers. Both rivers have been important salmon rivers. The oldest known salmon dam was located in the then mouth rapids of Simojoki, known as Patokoski, during the 1000s and 1100s. Simojoki is indeed one of Lapland’s oldest areas of permanent settlement. During the Middle Ages, the Kemi mother parish, later the Kemi parish, was a vast entity that extended as far as Rovaniemi and included the neighboring municipalities of Martimoaapa, Simo, and Tervola. For centuries in Haminasaari on the Kemijoki River, merchants from the Baltic Sea, local fishermen, and upland fur trappers met.

Fleeing from War

In the early 18th century, Russia occupied Finland, which was then part of Sweden. The ten-year occupation during the Great Northern War came to be known as the Great Hatred and the Greater Hatred. It was indeed a ruthless time of hatred. Peter the Great ordered the destruction of the coast of Ostrobothnia from Kalajoki northward for 100 kilometers, so that the Swedish army would never penetrate eastward through that route again.

In 1714, Russian forces captured Kemi, causing unrest and destruction. The Russians took church bells from several villages, but in Kemi, the church bells were taken down from the steeple and hidden before the enemy could get to them. Peasants also began to hide their belongings and build hidden shelters throughout the wilderness. Remnants of these hiding places and shelters can still be found in remote areas.

In Sirkonkangas, Tervola, remnants of escape shelters have been found in studies, and the story tells that the Russians had discovered and killed the people hiding there. In Simo, several households fled to the banks of the Viantienjoki River. Simo experienced fewer persecutions than, for example, Keminmaa and Tervola, because the people of Simo had already fled to hidden shelters well in advance. It was also fortunate for the people of Simo that the Russians did not keep as many troops there as in nearby villages.

During the Greater Wrath (Isoviha), a chain of beacon fires, known as the persecution fire chain or the beacon chain, extended from Karelia to the Tornio River. This chain of fires was used to warn inhabitants of enemy movements. One such beacon location was on the peak of Yli-Penikka, from where a lit fire could be seen all the way to the mouth of the Tornio River.

The Great Northern War ended in 1721 with the Treaty of Nystad, and life gradually returned to peaceful routines. However, all the horrors and cruelties of the war remained etched in people’s minds. The stories lived on in the names of places, and tales of the cruel years were still recounted as bedtime stories and during gatherings for years to come.

Stories from the time of the Greater Wrath are associated with the Kuolemankoski and Kalmakoski rapids of the Simojoki River, telling of how locals had tricked Russians into going over the rapids to their death. There is a story about Kellolampi (Clock Pond) and Kellolähde (Clock Spring) in which it is said that the church bells of Keminmaa were sunk there. A similar story is told about Simo. In Simo, there was no church tower built yet, and the church bell hung between two poles. According to the tale, the bell of Simo Church was hidden in Viantienjoki’s Kellolampi. It is said that even now, near the Clock Ponds, one can hear the ghostly ringing of a bell.

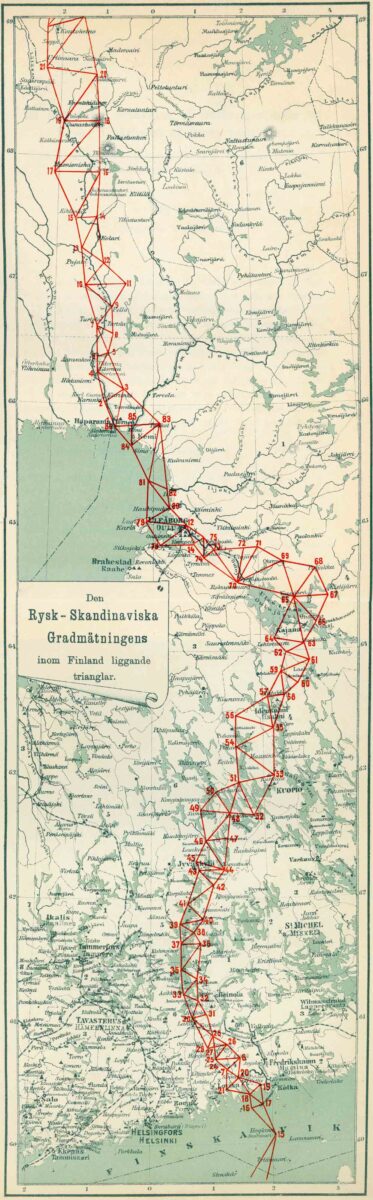

The triangular survey point of Ala-Penikka

In the 19th century, the shape and size of the Earth were determined using the Struve Geodetic Arc, also known as the Struve Arc. The Russian-Scandinavian triangle measurements began in 1816 from the Black Sea and concluded in 1855 at the shores of the Arctic Ocean in Norway. Finland is a long country, and therefore, one-third of the entire chain’s points are located in Finland. The Struve Arc is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and six of the selected measurement points are located in Finland.

In 1851, a group of scientists conducted triangulation measurements in Tornio at the church, Kaakamavaara, and Kivalo. This formed the measurement point number 83 of the Struve Arc, Kivalo, which was located on the slope of Ala-Penikka. So, the second starting point of the Perä-Pohjola triangle chain was located at Ala-Penikka. The other two points of the triangle were located at Ylä-Penikka and Palovaara. Later, the measurement points were combined, and the final triangle points of the chain were formed as Ala-Penikka, Ajos (at Kemi), and the church of Ala-Tornio.

The points of the chain were placed on hills or other high places with a good line of sight to the next point, and the distances and angles between the points were measured using triangulation. In Finland, the measurement points were marked by drilling one or two holes, a few centimeters in diameter, into the rock. Lead plates were attached to the holes with lead. However, lead was valuable material at that time, and according to stories, hunters wanted to remove them to use as materials for their own bullets. Therefore, not much lead or copper plates have survived, but the drill holes are still visible in the terrain at many points.

Observation points, or signals, were built at the measurement sites unless there was already a visible point, for example, church towers were used for this purpose. A wooden tower was built as a signal, and a barrel was attached to its top. Triangulation was a massive project involving thousands of conscripts, tower builders, surveyors, and other individuals. Many locals participated in the construction of the points.

The moonshine caravans

Peräpohjola, especially Kemi and Tornio, has been an important trading hub for centuries, both for the local region and for European merchant ships, and it has been and still is an important border crossing point. The more trade there was, the more desire there was to regulate it and collect tax revenues from it.

In 1809, the border between Sweden and Finland was drawn in the middle of the common Torne River, and of course, the border was monitored. Thus, a strong smuggling culture, known as “jobbaus,” emerged in Peräpohjola, as various products were smuggled across the border for both relatives and for sale. Fur and game, coffee, spices, butter, and spirits, and nowadays also snuff, were smuggled across the border.

In Finland, the right to distill spirits at home was abolished in 1886, and in 1919, prohibition was introduced, which prohibited the production and sale of spirits. This gave a significant boost to the spirits smuggling culture. The Finnish people did not simply want to become abstinent; quite the opposite. Therefore, moonshine, or homemade spirits, began to be imported from abroad, mainly from Germany. Kemijoki estuary and especially Simon’s Maksniemi became Finland’s busiest spirits smuggling center, the so-called “moonshine gateway.”

The spirits were first brought by sea to coastal islands, from where most of it was transported inland in so-called moonshine caravans. It is estimated that 30-40 men were constantly involved in such transports. Smuggling routes ran far from main roads to minimize the risk of getting caught. Although the journey was arduous, it was worth it; a liter of moonshine cost about ten marks on the moonshine boat, but in Rovaniemi, one could already earn 300 marks with it.

On land, smugglers transported moonshine by carrying it or using horses. The spirits were hidden in the load of hay, chopped bags, and milk churns. Large quantities of moonshine were also carried by, for example, small canisters hidden under clothes. The other name for a small flask, the “sparrow,” also dates back to those times. The sparrow fit nicely into a breast pocket, even when going dancing.

In the northern part of Martimoaapa, the moonshine caravans followed the secret Maksniemi – Sompujärvi – Tervola – Arppee – Kauhanen – Rovaniemi moonshine route. From the coast of Simon, they transported moonshine through the Viantienjoki river via winter roads and swamps, following the Kivalo hills all the way to Rovaniemi. The route is still visible in the terrain and follows the current snowmobile route in the upper parts of Martimoaapa.

Read next: Martimoaapa history part 3

Sources and more info:

- The National Library of Finland

- Kultuuriympäristön palveluikkuna, The Finnish Heritage Agency

- Aapa – Pohjoisten soiden kiehtova elämä, Lapin maakuntamuseon julkaisuja, 2019

- Simojoen virta-alueiden kunnostusalueet – arkeologinen ja kulttuurihistoriallinen selvitys, Keski-Pohjanmaan ArkeologiaPalvelu, 2015

- Keminmaan kunta, Puukkokumpu ja Sompujärvi sekä Asutusta yli tuhat vuotta artikkelit

- Lapin perinnemaisemat, Satu Kalpio ja Tarja Bergman, Lapin ympäristökeskus ja Metsähallitus, 1999

- Struve Geodetic Arc, a World Heritage Site, Visit Sea Lapland

- 300 vuotta sitten Pohjanmaalla tehtiin hirmutöitä, joista nyt tuomittaisiin kansanmurhana – “Raaimmista verilöylyistä jäivät todistamaan vain ruumiskasat”, Yle, 2021

- Historia tulee polulla vastaan – osa 3, Pentti Korpela, Kemi.fi, 2020

- Muistelmia 4:n Oulun Suomen Tarkkampuja Pataljoonan Jääkärikomennuskunnan karhunpyyntiretkeltä keväällä y. 1900, Lukemisia Suomen sotamiehille, 01.01.1901

- Trokareita ja kylttyyriä hankkeen loppuraportti, Outokaira tuottamhan ry, 2021

- Suomalainen paikannimikirja, Kotimaisten kielten keskus, 2019

- Simon kirja, Hannu Heinänen, Mauno Hiltunen, 1986

- Keminmaan historia, Pentti Koivunen, 1997

- Kahen puolen Kemijokea – Tervolan kunnan historia, Eemeli Hakoköngäs, 2017

- Pirtusota ja salakuljettajat, Juha Ylimaunu, 2022

- The Museum of Torne Valley

- Jatuli XIV, Kemin kotiseutu- ja museoyhdistyksen julkaisu, 1973

- Jatuli XI, Kemin kotiseutu- ja museoyhdistyksen julkaisu, 1967

Translated with ChatGTP

Write a comment