This story is the third part of the Martimoaapa history series. The series recounts the history of Martimoaapa and its surrounding area from ancient times to the present day, highlighting signs and memories that are still visible to travelers in the terrain, serving as reminders of times past.

Since the late 1800s, settlement has gradually spread to the surrounding villages of Martimoaapa. During the summer, the scythes of the mowers swayed on the grassy marshes, while in winter, the nearby forests were filled with logging sites, and in spring, the riverbanks were bustling with log drives. The swamps and forest patches were excellent hunting grounds, especially in autumn for hunting game birds. But more than just berries, larger prey roamed these marshes, which the legendary bear hunters of Simo sought to capture.

Gifts of nature

As the land rose from the sea, coastal meadows were exposed, enabling the development of cattle farming. From the 1600s onwards, peasant settlements and agriculture began to establish and expand from the banks of rivers into the inland.

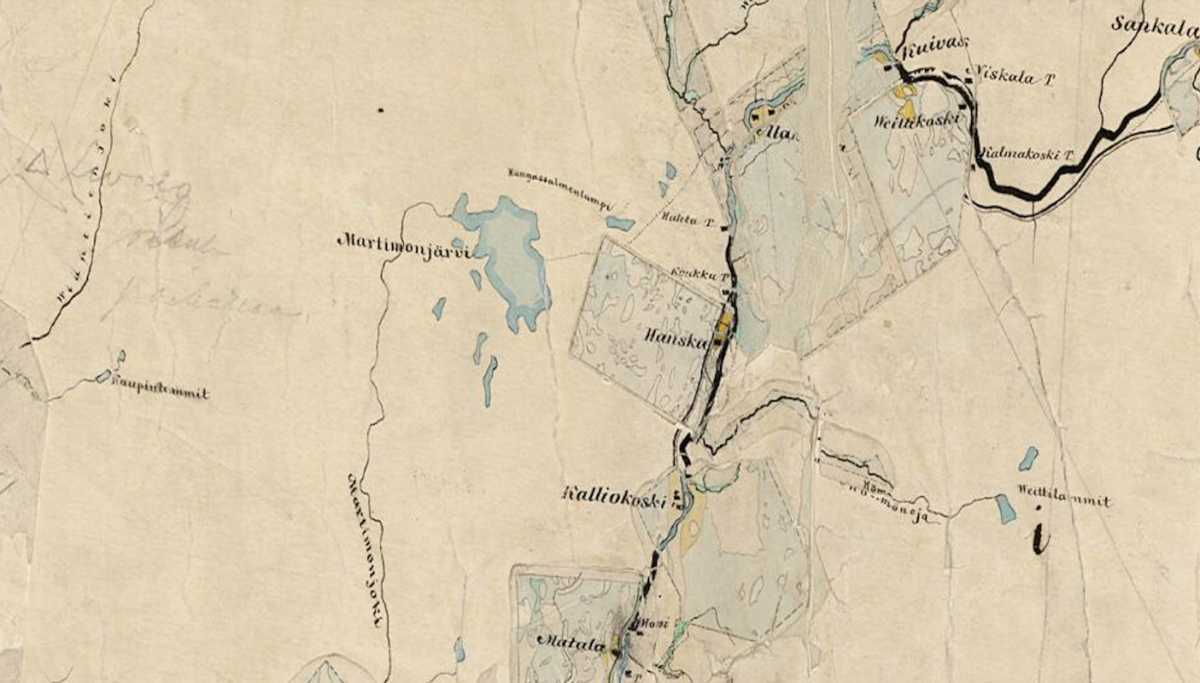

Rovaniemi separated from Kemi to become its own parish in 1785, and in the 1860s, the municipalities of Simo and Tervola were formed. Due to the land uplift, the mouth of the Kemijoki River became shallower, preventing merchant ships from navigating it, leading to the establishment of the city of Kemi by the sea in 1869.

The nearest villages on the outskirts of the Martimoaapa Nature Reserve are Pömiö, Alaniemi, and Puukkokumpu. Puukkokumpu and the next Sompujärvi, also known as the Kivalo village, are among the most remote residential area in Keminmaa. It is 36 kilometers from the center of Keminmaa to Sompujärvi.

Initially, settlement was concentrated along the riversides. Martimojärvi’s lower reaches saw the establishment of Martimo’s new farm as early as 1847, but the settlement spread to nearby villages only in the late 19th century. Initially, there were crown farms, later forestry worker estates, and after the wars, front-line soldier estates. A farm named Puukkokumpu was established in the early 1880s.

Settlement also spread to the banks of the Viantienjoki River. The Viantienjoki river flows west of the Penikat hills and empties into the Simojoki river. In 1851, Isopuute farm was established along the Viatienjoki River. The crofters lived along the riverbank, but the farmhand Johan Posti (1820-1898) resided on the farm. Next to Isopuute, a forest ranger’s house was built, named Apula. Johan Posti moved to live in Apula and worked as a forest ranger until retirement age. His duties included protecting the nearby forests and ensuring that no illegal activities, such as unauthorized logging, took place. Posti served as a forest ranger for over 30 years and received a forest ranger’s merit medal for his long service. His son, Lauri Posti (1858-1936), followed in his father’s footsteps.

Forestry and log-floating work were also a significant part of Apula’s additional income. In the early 20th century, the farm was the most thriving croft along the river, contributing to the spread of settlement along the Viantienjoki River. When the eldest son inherited the farm from his father, the younger ones had to seek livelihood elsewhere or establish their own farms, even if it meant settling nearby.

The scythes are swishing on the meadows

Before the widespread adoption of crop cultivation, here in Peräpohjola, hay was often harvested from natural meadows and marshes for fodder. The grassy marshes of the Martimoaapa area have been excellent places to gather straw, meadow hay, and sedge for fodder. One of the grazing areas of the aforementioned Apula farm was Pömiö, where fodder hay was harvested. Butter was an important commodity, both for personal use and as a supplementary income-generating product. Fodder increased the milk production of cows and was crucial for improving livelihoods.

Hay was usually mowed from the meadows using a scythe. It had a long handle and a blade assembly, which allowed for gathering the sparsely growing and soft marsh grass into piles. Once the hay had dried, it was gathered using a pitchfork or hayfork and stacked into haystacks or taken to the barn if there was one. Mowing the meadow hay was largely a manual task since horses couldn’t be of assistance on the marshy ground, except in winter when the hay could be transported from the marsh by sleigh.

A modern-day hiker can take a couple of tips from the haymakers of yesteryears:

- In the backpack, durable foods are packed.

For example, jerky, salted fish, potatoes, bread, and here in the Peräpohjola and Ostrobothnia regions, one could also bring along squeaky cheese. - Drinks stay well if submerged in a swamp.

Butter and buttermilk were common provisions to bring along. They were submerged in wooden bowls in the swamp for a day, where they stayed cool.

Many local farmers used to harvest hay in the marshes of Martimoaapa. The leased lands of the Alakärppä farm in Alaniemi, Simo, were located along the Martimo-oja stream and north of Koivuselkä, where the Alakärpä hay hut was also situated. The small cabin of Jussa at Koivumaa was likely the hay cabin of the Jussapäkki farm, located along the Simo River.

Penikanjänkä, stretching to the east of Keski-Penikka, also used to yield a lot of natural grass. At the edge of the marsh, there was the hay sauna of the Hast farm, used for gathering hay and bathing after long workdays. The hay sauna also served as one of the support points during the Jäger Movement. Through it, the Kivalo area is connected to the history of Finland’s independence, but more on that in the next blog post.

In the 1920s, there was a shortage of hay meadows in Simo, and more hayfields were acquired by draining ponds and small lakes. Plans were made to drain Martimojärvi and Maaninkajärvi. Out of these two, Maaninkajärvi was drained. Maaninkajärvi is located about 20 kilometers southeast of the Martimoaapa area, slightly south of Yli-Kärppä. About a hundred men dug by hand with shovels a canal over two kilometers long from Maaninkajärvi to the Simo River. The water flow in the canal was regulated by damming the outflow in spring, and before haymaking, the water was drained. The surface area of Maaninkajärvi is now about a fifth of what it was before draining.

In the Middle Ages, the peasants of Peräpohjola (northernmost Finland) had reindeer, but they were mainly used as a means of transportation. People from Peräpohjola engaged in a lot of trade with the Sami people. Reindeer husbandry itself became established only in the 19th century as a secondary occupation for locals.

In the Martimoaapa area, there was once a fixed reindeer fence on Poronpellonsaari island, now the reindeer fence stands south of Myllylänaho. During the summer, reindeer roam Martimoaapa grazing and seeking shelter from mosquitoes and midges on the open marshes.

Logger sites

The Finnish Forest Administration was established in 1859 to manage state-owned lands and entered into contracts with new settlers, defining the rights and obligations of tenants. Large-scale timber drives began in Northern Finland in 1872, and in the same year, the state allowed the establishment of crown forest crofts, or leased crofts for housing and agriculture, on its own lands. In Simo, there were already 22 forest crofts by the turn of the 1880s.

Later, timber drives were used to pay war reparations, and after the wars, wood was needed for the reconstruction of Lapland. In the 1920s, the paper industry experienced rapid development, increasing the demand for wood as a raw material. With a high demand for wood, timber drives were abundant.

The first water sawmill on the Simojoki River was Kalliokosken saha, founded in 1841. Sawmills were established in Kemi and Tornio in the late 19th century, and one of the largest companies in the area was the Kemi Yhtiö.

Forestry work was an integral part of the rural work rhythm. In the autumn, when the workload on the farms eased, people headed to the forests for timber drives. Logging usually began in November and ended in March. Forestry work provided a good source of additional income.

This led to the development of a professional forestry workforce, from loggers to teamsters and from timber rafters to surveyors. Loggers were mostly itinerant workers, while teamsters were locals. The work of a timber driver was heavy. In the 19th century, trees were felled using only axes. Crosscut saws, operated by two men, appeared in many sawmills only after the wars. The logs were transported by horses to storage locations closer to the road or river, from where they continued their journey forward.

The forest patches dotting the marshes of the Martimoaapa area have almost all been utilized for forestry purposes, resulting in relatively young tree stands. The trees are mostly planted from the 1950s to the 1960s. There were also forestry work sites in the slopes of Penikka and along the banks of Akkunusjoki river west of Yli-Penikka.

The so-called “cabin law” came into force in 1920. According to it, living quarters had to be built for logging workers on the construction site. In his memoir “Nuoruuteni savotoilta,” K.K. Korhonen recounts how in the small logging cabin by the Akkunusjoki river, there was a “tight atmosphere” when the damp, smelly, and sweaty clothes of 30 men hung all around the cabin. The greasy smell of fried bacon gravy from the stove added to the atmosphere of the cabin. Later, as logging became mechanized, the cabins quietly disappeared from the forest landscape.

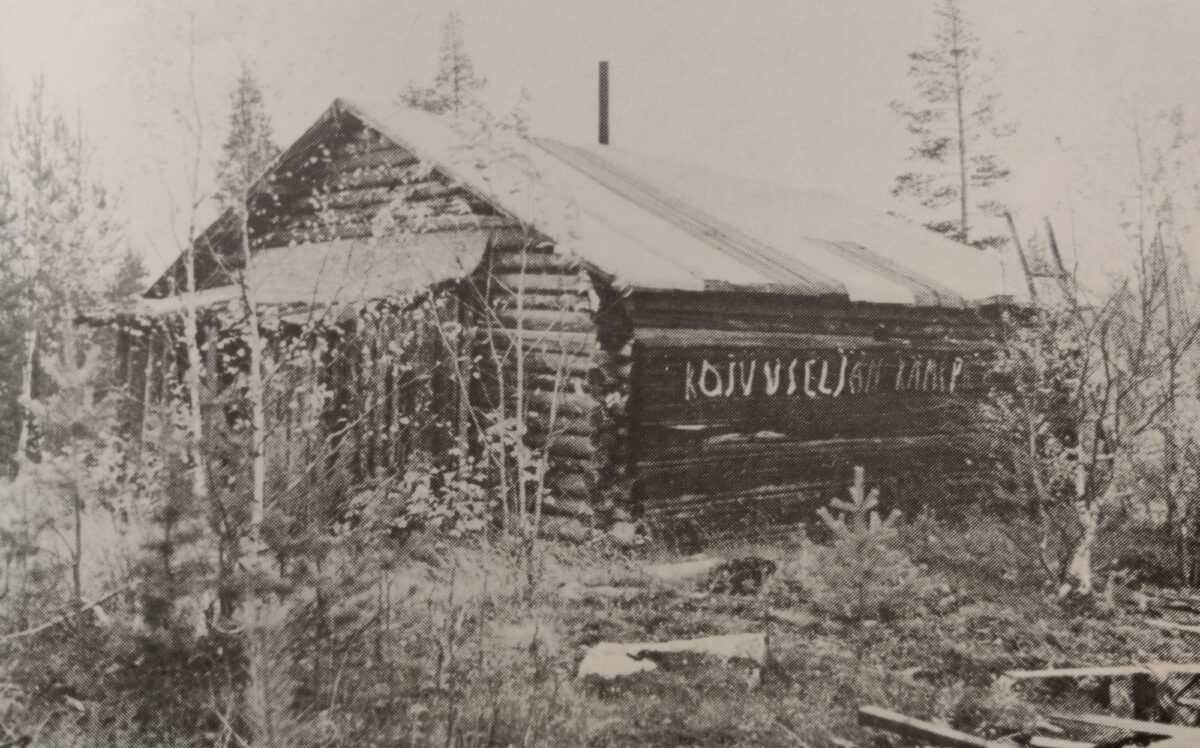

In the Martimoaapa area, there were two logging cabins, one in Koivuselkä and the other in Saunasaari. The Koivuselkä logging cabin was built in the early 1950s by the Oulu companies, and it was dismantled as early as 1995. The Saunasaari logging cabin was designed for 24 people. It included a cabin equipped with bunks, a kitchen, and a drying room. Heat was provided by a stove, and light for dark evenings came from Tilley lamps and kerosene lamps. The Saunasaari logging cabin was moved elsewhere long ago, but the main cabin sauna still remains. The logging cabin sauna was built in 1947 and includes an entrance hall and sauna section. Both cabins were renovated for recreational use after logging operations ceased.

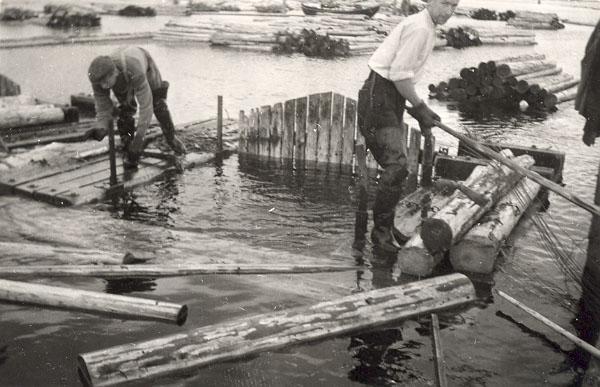

Logging was also associated with log drives, which were used to transport logs to sawmills. When logging activities wound down in March, as soon as the spring floods began, logs were floated down streams and rivers to the banks of larger rivers. The main log drive routes in the Martimoaapa area were along the Kemijoki and Simojoki rivers. Log drives were at their peak in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but from the 1970s onwards, they began to decline, and log transportation shifted to trucks and railways.

Log drives were already being conducted on the Viantienjoki river in the 1800s, mainly by the owners of the Simon Vasankari and Kallio steam sawmills, who floated logs from the surrounding areas. In the 1930s, the river was dredged to remove rocks and boulders using dynamite to facilitate log drives. After the wars, the river was also dredged for flood protection, and its course was straightened.

Dredging and blasting have left the Viantienjoki river in rather poor condition. Restoration work was carried out on the river in the early 2000s, and last year (2023), restoration activities were undertaken on the upper reaches of the river in Kurkioja. Kurkioja originates from the peatlands amidst the Penikat hills, and about ten kilometers of the stream is located within a protected area. The goal of the restoration efforts is to improve habitat conditions, particularly for sea trout.

Hunting in the wilderness.

The wilderness, as such the marshes and forested areas of Martimoaapa are called, originally referred to a hunting ground. The wilderness was a designated hunting area associated with a particular family, village, or other entity, where its owners had the right to hunt, fish, and set traps.

Initially, the surroundings of Martimoaapa were hunting grounds for nearby villages and estates. Here, squirrels, ermines, beavers, hares, otters, and foxes were hunted. Significant game also included forest birds, especially capercaillies, which were valuable prey. They were caught using various traps and snares. The traps were economically advantageous because there was no need to wait all day or chase after prey; instead, one could focus on other tasks while the traps yielded catches on their own.

Fishing, hunting, and gathering other natural resources have long traditions. The moose is depicted as an important animal already in Stone Age rock paintings. Previous generations can indeed be considered as moose people, but waterfowl, bears, and other game have also played a central role in forestry and nature worship.

Fur trapping was also thriving throughout the 19th century. Pelts and furs were traded in coastal ports, but taxes were also paid on them. The Crown had the right of first refusal for furs. Squirrel, ermine, and beaver were valuable catches. Thus, in some places, populations were quite low, and the beaver was nearly hunted to extinction by the mid-19th century.

Furbearing animals were caught with various traps and snares, and later with traps made of iron. Fox paw boards remained in use alongside iron traps for a long time. A paw board was a two-meter-long piece of wood or stump with three sharp-pointed spikes carved at the top, the middle one being longer than the others. The bait was placed on the middle spike, so when the fox reached for the bait, its paws got caught on the board. The use of paw boards was prohibited in the hunting law reform of 1934.

During an archaeological inventory in 2007 near Hangassalmi, a keloid fox paw board was found on an adjacent forest islet. The board was about 2.5 meters high and 30 centimeters wide. Its upper part was slightly damaged, but one side spike and the middle spike were still intact.

Bear hunters from Simo

The Martimoaapa area has been an excellent living room for bears since the formation of the marshes. It has been a peaceful place for them to wander and munch on berries, occasionally disturbed by humans.

Seeing a bear in the wild was interpreted as a sign of luck and success, and many stories were told about bear hunting expeditions. These tales often revolved around overcoming the forces of nature and a clever opponent, highlighting the hunter’s skill and determination. Simo bear hunters were renowned for their skills and bravery. People traveled from Oulu and even Turku to Simo to hunt game and face legendary bear hunters eye to eye.

One of these legendary figures was Sanka-Jussi, or Juho Sankala (b. 1805), a woodsman from Simo, skilled blacksmith, and legendary bear hunter. It is said that Sanka-Jussi killed his first bear at the age of 12 and went on to hunt over 50 bears and an equal number of other predators in his lifetime. The stories of Simo’s “Hosion-ukko,” or Erkki Hosio (b. 1832), and Kuivas-Jussi (b. 1838), are also part of local cultural history. According to legend, Hosion-ukko, unarmed when encountering a bear in the forest with a friend, chased the bear, climbed onto its back, and held onto its ears until his friend arrived with a gun.

Many place names in Martimoaapa indicate that bears were once a part of the area’s wildlife, and perhaps legendary hunting tales inspired their names. There are, for example, Karhunpesänsaaret (Bear’s Nest Islands), Kontiokummut (Bear mounds), Errauksen-Penikka (Bear cup), and of course, the most famous, Penikka Hills (Bear Cub Hills). While bears may still roam the forests of Martimoaapa, the increase in visitors to the area may have encouraged them to stay further away in more remote areas.

Read next: Martimoaapa history part 4

Sources and more info:

- Martimoaapa‐Lumiaapa‐Penikat Natura, Kulttuuriperintökohteiden inventointi 2007, Metsähallitus

- Martimoaapa history, Nationalparks.fi, Metsähallitus

- The National Library of Finland

- Historia tulee polulla vastaan osa 4, Pentti Korpela, Kemi.fi, 2020

- Suomalainen paikannimikirja, Kotimaisten kielten keskus, 2019

- Kemin seutu, dokumentti, Veikko Laihanen Oy, Elonet, 1963

- Puukkokumpu ja Sompujärvi, Keminmaan kunta,

- Lapin perinnemaisemat, Satu Kalpio ja Tarja Bergman, Lapin ympäristökeskus ja Metsähallitus, 1999

- Kultuuriympäristön palveluikkuna, The Finnish Heritage Agency

- Muistelmia 4:n Oulun Suomen Tarkkampuja Pataljoonan Jääkärikomennuskunnan karhunpyyntiretkeltä keväällä y. 1900, Lukemisia Suomen sotamiehille, 01.01.1901

- Kaivurit möyrivät Simon Kurkiojan uuteen uskoon taimenten lisääntymispuroksi, Lapin Kansa, 25.09.2023

- Simossa ja Keminmaassa virtaava Kurkioja on moniongelmainen puro, jonka mittavien kunnostustöiden tavoitteena on saada meritaimen takaisin, Yle.fi, 21.9.2023

- Nuoruuteni savotoilta, K.K.Korhonen, 5.8.20024

- Isien työt, Kustaa Vilkuna, 1953

- Simon kirja, Hannu Heinänen, Mauno Hiltunen, 1986

- Keminmaan historia, Pentti Koivunen, 1997

- Kahen puolen Kemijokea – Tervolan kunnan historia, Eemeli Hakoköngäs, 2017

- Jatuli XIV, Kemin kotiseutu- ja museoyhdistyksen julkaisu, 1973

- Jatuli XI, Kemin kotiseutu- ja museoyhdistyksen julkaisu, 1967

Translated with ChatGTP

Write a comment