This story is the fifth and the last part of the Martimoaapa history series. The series recounts the history of Martimoaapa and its surrounding area from ancient times to the present day, highlighting signs and memories that are still visible to travelers in the terrain, serving as reminders of times past.

In the late 1930s and especially after the wars, the development of national tourism and its possibilities began to emerge in Finland. Various skiing and downhill skiing trips to the Penikkavaara hills were organized from nearby areas. In the 1970s, there was a ski slope with lifts at Keski-Penikka, and hiking trails were built. At the same time, there was also a growing interest in nature conservation. The Martimoaapa mire conservation area was established in 1981.

Let’s go slalom skiing to Kivalo

The late 1930s marked the golden age of tourism in Finland. Hotels and tourist lodges sprung up like mushrooms after rain, national parks were established, and hiking trails were marked. Downhill skiing and wilderness hiking were popular activities. In 1938, the Finnish Tourist Association had thirty offices across Finland and was one of the largest promoters of tourism. New routes and hiking structures were planned to be ready for the 1940 Olympic Games, but the Winter War disrupted the plans.

In addition to cross-country skiing, slalom skiing, also known as downhill slalom or slalom skiing, became popular in the late 1930s. Downhill skiing and slalom skiing became official disciplines for the first time at the 1936 Winter Olympics in Germany, inspiring skiers to hit the slopes and weave through gates.

The Penikka hills were a popular skiing destination already at the turn of the century. For example, teachers from Kemi and the Civil Guard (Suojeluskunta) organized skiing trips to Ala-Penikka. When the local branch of the Finnish Tourist Association, Kemi Tourist Association r.y, was established in Kemi in 1937, it further increased the number of visitors to the Penikka hills. The Kemi Tourist Association focused on improving transportation links and tourism services, producing numerous tourism brochures and guides, and organizing exhibitions.

In 1945, the Tourist Association began planning a skiing and hiking lodge on the slopes of Ala-Penikka. The city of Kemi provided a barrack for the use of the Tourist Association. It was renovated and had 40 beds. The lodge was popular and well-used, but in 1949, a settlement was established nearby, whose residents requested the lodge to be moved. Since the lodge was in poor condition, and relocation was not feasible, it was decided to sell it. The Ala-Penikka tourist lodge was in operation for only a few years.

Ala-Penikka was a popular skiing and hiking destination, and at its summit stood a fire lookout hut and tower. In the mid-1950s, a radar station for the Finnish Defense Forces, Lapland Air Command, was installed on Ala-Penikka. After the radar station was established, the fire lookout hut and tower were moved to Keski-Penikka. Thus, hiking activities mainly shifted from Ala-Penikka to Keski-Penikka. Ala-Penikka area remained unfamiliar to many hikers because during the radar station’s operation, there was no access to the area.

Kivalo’s recreational center

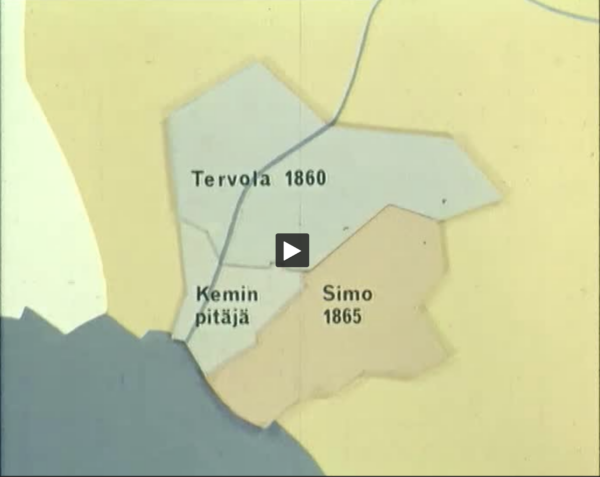

The popularity of Kivalo as a skiing and hiking destination continued to grow, prompting plans for the area’s development in the 1970s. In 1968, Ulkoilu-Kivalot Oy was established to lead the development of the Kivalo outdoor and recreational area. Ulkoilu-Kivalot Oy was a joint-stock company whose shareholders included the city of Kemi, Kemi Oy, Kemin rural municipality, the municipality of Simo, several professional associations, and private individuals. Its operations were supported by funds from Veikkaus, the Finnish national betting agency.

The first private building in Kivalo was erected in 1968 when the Kemi Tourist Association’s (Kemin Matkailijayhdistys r.y) cabin was built in Kivalo. The logs for the cabin were brought from Tervola, and the cottage was reassembled on the slopes of Keski-Penikka. The Finnish Forest and Park Service (Metsähallitus) granted approximately 850 hectares of land to the Tourist Association. Later, the cabin was transferred to the ownership of Ulkoilu Kivalot Oy. The cabin served as the Kivalo recreational center and café with refreshments, functioning as the base for the ski resort.

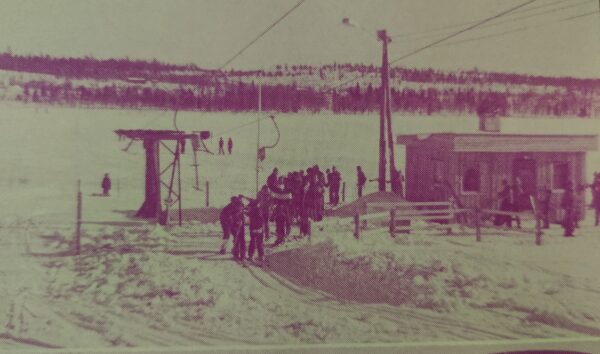

The lodge was located on the slope of Keski-Penikka, and the ski slope was cleared next to the lodge. Pioneers practiced explosions in clearing the ski slope. After the clearing, the slope was leveled with humus accumulated during the excavation of the Penikka ponds. The Penikka ponds are the artificial ponds visible on both sides of Oravankankaantie when approaching the Kivalo parking lot. The ponds were built to enhance the landscape and provide swimming and fishing opportunities for future tourists.

The ski slope featured a 350-meter-long anchor tow lift with a height difference of 62 meters. The lift was purchased from the city of Helsinki and put into operation in 1975. In the Kivalo outdoor area, there were also several vacation cottages owned by various organizations, including the Lions Club of Kemi, the Kemi Teachers’ Vacation Home Association (Kemin opettajin Lomatupayhdistys), and Keminsuun Auto Oy.

Ulkoilu Kivalot Oy had ambitious plans for the development of the Kivalo area. A comprehensive outdoor center was planned for the Keski-Penikka area. The plans included the construction of a hotel for 200-300 people with dance floors and conference facilities, a camping area, and a holiday cottage quarter for tourists. Outdoor facilities were planned for orienteering, fitness enthusiasts, and various sports competitions, including even reindeer racing.

However, the grand plans were thwarted, and for years, the Kivalo ski resort enjoyed quieter times. The skiing boom lasted only a few years in Kivalo, and soon almost all the structures, including the ski lifts, were dismantled.

In the early 1990s, Lapponia Safaris purchased the vacant Kivalo outdoor lodge. The company renovated the lodge and set up a teepee village in the yard. The lodge accommodated 25 overnight guests, had a restaurant, and outside, there were five teepees and a sauna. The place became a popular stopover for foreign tourists on hiking trips and snowmobile safaris.

Wetland conservation

Most of Finland’s bogs have formed over thousands of years since the end of the Ice Age. New bogs are no longer forming except on the post-glacial rebound coastline. Currently, about 29% of Finland’s land area is covered by bogs. The area would be larger if bogs hadn’t been drained so vigorously in the early 1900s. Especially after the wars, rapid population growth and settlement activities accelerated the clearing of fields.

In the 1960s, attention turned to the preservation and protection of bogs. The joint Bog Conservation Committee of the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation (Suomen Luonnonsuojeluyhdistys) and the Finnish Peatland Society (Suoseura) conducted extensive surveys and negotiations with the Finnish Forest and Park Service (Metsähallitus) to preserve bog sites. A national program for bog conservation was completed in the early 1980s, and various organizations began to inventory and advocate for bog conservation. Some bogs were protected as national parks, while others became part of forest conservation programs, bird habitat protection programs, or water protection programs.

The Martimojärvi mire area was designated as one of the 12 Finnish sites in the international Project Mar program, and the implementation of its protection was covered by the Convention on Wetlands treaty signed in 1965. The program aims to protect waterfowl and wader breeding and migratory stopover areas.

As a side note, it seems that compiling a list of Finnish wetlands was not entirely straightforward, as noted in the 1965 Project Mar report: “Because of the extremely complex situation in Finland with its c. 62,000 lakes, numerous islands and irregular coastline, it has not been possible to compile a complete wetland list on the same basis as in other countries. The number of wetlands in Finland is so vast and in consequence the fauna so scattered that there is not enough comparative material available on which to base a list.”

The establishment of the Martimoaapa Mire Conservation Area

The establishment of the first protected forests and “nature reserves” in Finland began in the early 20th century, and nature conservation was incorporated into law in 1923. The first official mention of establishing national parks dates back to 1910, and the first national parks were established in 1938.

The development of national parks was in full swing by the 1970s. The Martimoaapa area was proposed as a national park at that time. Martimoaapa, or officially Martimojärvi National Park, was included in the 1973 Environmental Protection Negotiating Council’s proposal for the development of Finland’s national park network, and the Martimoaapa area was one of the targets of the Finnish Academy’s (Suomen Akatemia) national park working group. However, the matter did not progress at that time. The issue is brought up for discussion from time to time. Last year (2023), the Kemi-Tornio Birdwatchers Association (Kemi-Tornion Lintuharrastajat) proposed converting the Martimoaapa conservation area into a national park.

In the 1970s, during the so-called peak years of peatland conservation, efforts began to protect and inventory the Martimoaapa environment more closely. The Ala-Penikka-Kivalo natural conservation forest area, known as the “aarinosa,” was established. The majority of the Martimojärvi mire area was protected from drainage, and the state-owned lands in the area were protected from hunting. South of Hangassalmennaho, there was a cloudberry test area maintained by the University of Turku and the Finnish Forest Administration’s Kemi management area. Later, the old-growth forest area, Kontiokummut, was incorporated into the conservation area.

In 1971, Finland joined the international Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. The Ramsar Convention requires the establishment of nature reserves for wetland countries and promotes the protection of internationally significant wetlands and waterfowl. Today, Finland has 49 Ramsar sites.

In 1981, over 70 state-owned peatlands were protected by law, one of which was the Martimoaapa mire conservation area. The Martimoaapa mire conservation area was incorporated into the Natura 2000 network in 2004, thus becoming part of the Ramsar Convention. Additionally, the Martimoaapa area was designated as an SPA (Special Protection Area), meaning it is a special protection area under the Bird Directive of the Natura 2000 network. The Natura 2000 network of sites protects important habitat types and species across the European Union, with the goal of preserving biodiversity. The conservation objective of the Martimoaapa mire conservation area is to maintain the natural state of the bogs.

Nature conservation was long part of Metsähallitus as part of forestry operations. Its own nature conservation office was established in 1981, and 10 years later, it was converted into a nature conservation department. Currently, nature conservation tasks as well as recreational services in Metsähallitus are managed by the Nature Services unit.

Hiking trail network

Hiking hobby became more popular after the Second World War, as mentioned earlier. After the wars, leisure time increased and living standards rose. Consequently, the establishment of various camping sites became necessary. During the peak years of tourism in the 1970s, Metsähallitus invested in expanding the wilderness hut network. Finland has a truly comprehensive wilderness hut network, and its breadth is unique on a global scale.

Metsähallitus reserved an area of about 3000 hectares for outdoor and hiking purposes in the Kivalo and Martimoaava areas in the late 1960s. At that time, a 50-kilometer hiking trail was established: the Martimoaava hiking trail from Kivalo to Hangassalmi, from Keski-Penikka to the route to Kaltiolampi and further to the Kemi-Puukkokumpu skiing trail, and from Kivalo to the route to Jatulinlehto. Additionally, a fitness trail was built along the Penikanoja River.

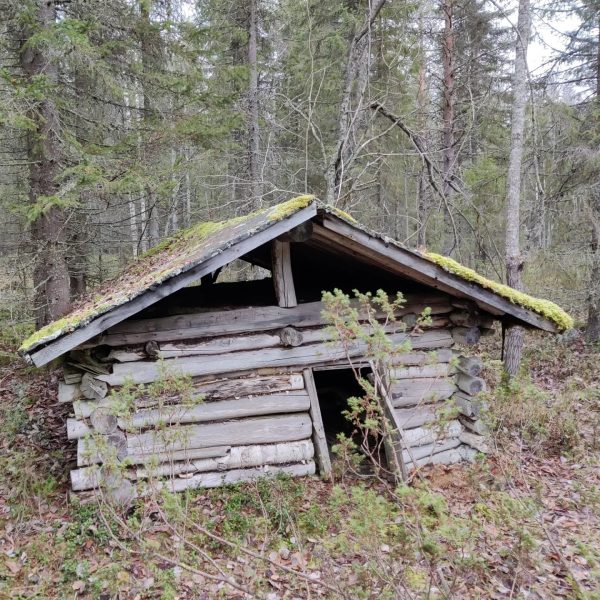

During the peak of domestic hiking in the 1970s, there were even more wilderness huts in Martimoaava than there are today. There was a rest hut on the ridge south of Lake Martimojärvi. On top of Yli-Penikka, there was a barracks-style lookout hut. In the Koivumaa area between Kivalo and Saunasaari, there were two huts. The Koivumaa hut, which had a sauna, kitchen, and a bedroom for 20 people, and on the eastern side of Koivumaa, still standing in the middle of the forest as a collapsing shack, was the small Jussa’s hut. Jussa’s hut is likely the old hay barn of the Jussapäkki estate established in 1924. The huts in Koivumaa and Martimojärvi have disappeared from the landscape.

The old logging cabins of Koivuselkä and Saunasaari were still in recreational use in the 1970s. Although the logging cabins no longer exist, new wilderness huts have been built in their locations. The Koivuselkä hut was built in 1992 in Posio as part of a log construction course and the Saunasaari hut was built in the 2000s. The original Saunasaari logging sauna is still barely standing, but it is not in use. The sauna is a museum building that will not be demolished but also won’t be restored.

The Lautiosaari-Puukkokumpu skiing and hiking trail runs from Puukkummu to Kivalot, then to Juokuanvaara and from there to Kemi. The trail is 36 km long. The route was originally planned by the Forest Center and built by the municipality of Keminmaa together with local forestry students in the mid-1990s. Currently, the skiing trail of the route is maintained by the municipality of Keminmaa.

The Border to Border skiing event has passed through Kivalot on several occasions. In the event, participants ski through Finland from the Russian border to the Swedish border, covering approximately 420 kilometers, and the ski tour lasts for 7 days. The Border to Border skiing event will be organized for the 39th time next year and has evolved over the decades into an international skiing event.

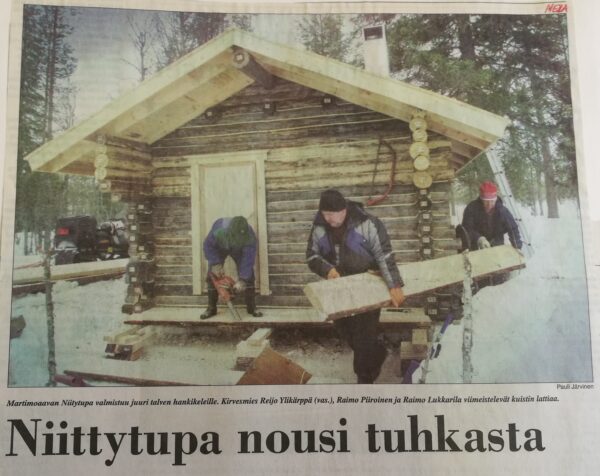

In the 2000s, a new meadow hut was built by the Martimo stream when the previous meadow sauna burned down the previous year. Initially, there were no plans to rebuild the hut, but construction began somewhat independently, and the locals collected nearly 300 signatures demanding the construction of the hut from Metsähallitus. The burned-down hut was originally built in the 1800s, known as Bööki’s sauna or Aapo’s hut.

In Kaltiolampi, there was still a hut with a sauna in the 1970s, the former Metsä-Botnia’s (Kemi Oy) cabin, but it eventually fell into disrepair. The collapsing hut was finally demolished in 2018, and the following year a hut from Pisanvaara Nature Reserve was relocated to the site.

On August 29, 2009, the inauguration of the Järviaapa Ring Trail was celebrated. The 9km long trail encircles Järviaapa. The Järviaapa trail has become a popular day hiking route. The trail consists mostly of duckboards, is suitable for a day trip, and offers views of the expansive bog landscape.

In the early 1990s, a designated boat storage area was established on the shore of Lake Martimojärvi. Over time, a considerable pile of boats, mostly in poor condition and abandoned, accumulated on the shore. Duckboards leading to the boat harbor were built in 1999. The popular Valkama lean-to, built in the early 2000s, located on the shore, burned down in 2018.

The most recent addition to Martimoaava was implemented a couple of years ago: an accessible trail from Hangassalmennaho to the edge of Järviaapa, along with an accessible open shelter (avokota) along the trail. The one-kilometer route is partially gravelled, with some sections consisting of transverse boardwalk structures. The trail is easy to navigate with a wheelchair, walker, or baby stroller.

All of the lean-tos in Martimoaava are small, accommodating 2-6 people, as they were designed based on usage patterns from the 1990s and 2000s. Fortunately, in addition to the lean-tos, there are also six fire pits (laavu) in the area for the enjoyment of hikers. There are a few other shelters and lean-tos in the vicinity, but they are not maintained by Metsähallitus and are not for public use. Along the Lautiosaari-Puukkokumpu skiing route, there are also several resting spots, but these are located outside the Martimoaava protected peatland area.

Closing words

Martimoaava’s history blog post was supposed to be published in 2021, marking the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the Martimoaapa mire protection area, coinciding with the peak of the hiking boom spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic. The plan was to celebrate the milestone and highlight this wonderful conservation area. However, delving into history drew me in, and what was initially planned as a single blog post expanded into a series of five, extending the writing process longer than anticipated. Well, as they say, better late than never.

Through this series of historical articles, I hope you’ve had the chance to delve into the past of the Martimoaava area, getting acquainted with ancient travelers and witnessing the development and significance of the area for wilderness enthusiasts, local villagers, and hikers alike. The bogs and surrounding nature have a history spanning thousands of years, often overlooked as we traverse the boardwalks and gaze upon the vast Finnish landscape.

I’ve roamed around Martimoaava for countless years. I hope to continue enjoying the area for many more to come; hiking, skiing, marveling at nature, and relishing the warmth of the huts. Exploring its history has opened my eyes to observe the environment more closely. With each visit to Martimoaapa, I discover something new to marvel at and experience, which is truly amazing.

Sources and more info:

- Martimoaapa‐Lumiaapa‐Penikat Natura, Kulttuuriperintökohteiden inventointi 2007, Metsähallitus

- Aapa – Pohjoisten soiden kiehtova elämä, Lapin maakuntamuseon julkaisuja, 2019

- Martimoaapa history, Nationalparks.fi, Metsähallitus

- Paahde-LIFE –alueiden kulttuuriperintöinventointi Sota-aavan ja Martimoaavan-Lumiaavan-Penikoiden soidensuojelualueilla 2014 ja Joutensuon Natura 2000 -alueella 2015, Metsä.fi

- Project Mar, The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 1965

- Kemin seutu, document, Elonet, 1963

- Historia tulee polulla vastaan osa 4, Pentti Korpela, 2020, Kemi.fi

- Koronapandemian vaikutukset suomalaiseen luonnossa liikkumiseen ja luontoliikuntapalveluiden tarjoamiseen, Jussi Muittari, Humanistinen ammattikorkeakoulu, 15.12.2021

- Simossa avataan uusi retkeilyreitti, Yle.fi, 27.8.2009

- Martimoaapa ja Sammuttijänkä kosteikkoluetteloon, Yle.fi, 2.2.2004

- Kemin opas, Kemin Matkailijayhdistys r.y., 1938

- Kantapuu-museoiden kokoelmat, Kansallisarkisto

- Martimoaapa–Lumiaapa–Penikat Natura 2000 -alueen hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma, Metsähallitus, 2010

- Nordic wetland conservation, Nordic Council of Ministers, 2004

- Vetoomus autiotupien ja kammien puolesta, Tunturilatu ry, 2016

- Border to Border ski, rajaltarajallehiihto.fi

- Autiotupavetoomus, Tunturilatu ry, 2016

- Luonnonsuojelulain nojalla vuosina 1978-1984 rauhoitetut luonnonsuojelualueet ja luonnonmuistomerkit, Ympäristöministeriö, Matti Osara, 1989

- Penikat huokuvat luonnonrauhaa: Kivalon 70-luvun lasketteluhuuma suurine suunnitelmineen vaihtui retkeilyyn ja safareihin, Pohjolan sanomat 2.7.2006

- Kivalon vapaa-aika-alue brochure, Kivalon Ulkoilu Oy, 1978

- Simon kirja, Hannu Heinänen, Mauno Hiltunen, 1986

- Keminmaan historia, Pentti Koivunen, 1997

- Kahen puolen Kemijokea – Tervolan kunnan historia, Eemeli Hakoköngäs, 2017

- Jatuli XVI, Kemin kotiseutu- ja museoyhdistyksen julkaisu, 1997

- Jatuli X, Kemin kotiseutu- ja museoyhdistyksen julkaisu, 1966

- Metsähallitus

- Simo library magazine and local archives

Translated with ChatGPT

Write a comment